Congrats! You’ve received your first draft for a record deal. It’s the industry standard, the label said. They even chipped in some extra money in the form of an advance, because they really think you are worth it. The big question is? Should you sign it? In the back of your head there’s a little voice whispering that you should be a bit careful with these kind of contracts and that copyrights are an important way to gain economic benefit from your day and night studio sessions. That little voice was hopefully mine, speaking to you at Dancefair or on some podcast on SoundCloud about music rights and the importance of screening your contract before signing it. If not, I’ll tell you a bit more about record deals in this blog.

“Do you want it and if you had it, would you flaunt it?”

Did you ever ask yourself the question why you would need a record label? Because they have great reach probably and they can get your track on their channels and possibly also on others? That’s right and well, that’s the first thing that you should define in the contract: what is the record label going to do exactly? Not more or less, but as accurate as possible and as much as possible. For example, will what will the label do to exploit the track? Will it also collect the money and arrange video shoots and synchronisation deals? Will it provide marketing budget?

And if you’re going to flaunt, please check the credibility of the label first. Who’s behind it, where do you need to be if any problems arise? If you’re a bit wary about it, it should make you stronger in the negotiations about this and future record deals.

Grant of rights in record deals

The record label will need to be able to exploit your track. In order to do that, they will need to have the right to do that and you can grant them that right either by transferring your music rights in and ownership to the master to the record label or by granting a license based on the same idea. The difference between transferring the ownership and granting a license is that you will remain to be the owner of the master and music rights when you grant a license, and you’ll lose that ownership by transferring the rights. It’s like selling a house and leasing one.

Another thing in this section of your contract will be about the exclusivity. If you are producing music in different styles or when you’re flirting with other labels too, you might want to keep the deal non-exclusive. It gives you more freedom. In an ideal world, you should seek a grant that is as short as possible, for example, the label would have rights for between three and five years to exploit a recording. When the contract ends, make sure you get all your rights back and that you are able to use any works, video’s, remixes, artwork, et cetera that was created during the term of the contract. Besides the grant and the term, playing with the width of the territory can create freedom for you as well. Is the record label really the best partner to exploit your track in Germany or would you like to have a local player with more credibility over there?

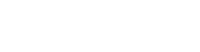

Music rights

Ok, so then it’s key to describe what rights you will be transferring of granting. To explain that part, we need to take a closer look to what rights are incorporated in a track. First there’s the copyright on the composition of the music and for example the lyrics. The copyright is usually split in the writers share and the publishers share. If you do not have a publisher or if you are your own publishing company (you need to be registered like that in the Dutch Chamber of Commerce trade register), you will have both shares in one hand. Try to keep it like that. Then, there’s the neighbouring right on the performance and the phonogram, the first recording, also called the master. At last, there’s physical ownership of the master. If you create the master at home, you are the owner, if it’s created in some studio or the labels studio, that studio owner or the label will be seen as the master owner, since the label has guided the recording and took economical risk in making it. A publisher is handling the copyright part and a label is handling the neighbouring rights and ownership part. Regarding the collective rights societies in The Netherlands, copyright and publishing things in go by Buma/Stemra and Sena is doing the neighbouring rights part.

For each part, the record deal needs to be very clear on what rights are transferred / licensed to the label and for what time. So, we’re talking about neighbouring rights, yes? There are different ways of working together with a label. Either you make a deal where you will be signed for 3 years or so and within those 3 years, you will need to transfer all your (neighbouring) rights on your tracks to the label and the label will be able to exploit the tracks for 30 years after release or so. You can also make a deal in which you only work together on certain tracks, an EP or an album and do this for a couple of years. There no “good” or “bad” in this, the deal just needs to be in balance with what you give and what you get. A shorter term usually means getting less, a longer term usually means getting more. Think about it. What if you want to leave after a couple of years or if you see this deal as a step up to the big boys league? Then a long deal might be bad for you.

You’re the boss

The goal of the deal is successful exploitation of your music. But what happens from that point on? Try to make very precise arrangement about who collects the money, when, who’s responsible, what the pay-out is, what are the royalty’s based on (for example the published price to dealer or “PPD”), what costs can be deducted and for example how gross and net are calculated. Not only for these arrangements, but in general for everything the label wants to do with either your rights, music or money, you should try to stay in charge and add to the contract that before giving away any rights or makings any costs, the label needs your prior written approval. Remember that, stay in charge!

Just one more point about the money, if it’s a big deal or your record goes boom, you might want to have the right to check the administration of the label annually. If there’s a difference in statements and pay-out, they need to pay all the costs for the accountant who has found your lost money. Unfortunately, this happens.

Money, money, moneyyy… Money!

There are three more things I want to elaborate about. The first is advances and I’ll be short about that one. If you don’t need it, don’t take it. It’s a loan and you’ll have to pay it back (or “recoup” it) by the income that’s generated with your music. It’s not a gift, keep that in mind, please. In Dutch we call it “a cigar out of your own box”.

Record deals & the tricks

The second thing I want to address is the controlled compositions clause and words about “statutory rates”. It’s a US thing and not beneficial for you as a musician / songwriter. These clauses are made to cap the money a label has to pay you regarding the tracks of which you are the copyright holder as well. If you can delete them, do it. To make it extra confusing, in the US they generally speak about copyright and not about neighbouring rights to a phonogram.

The third and last item you need to know a bit more about is options and lifting them. If there are options in the contract or if you have the obligation to transfer your tracks to the label, ask yourself what happens if an option is not lifted or if a track is either not approved or will not get released. In that case, get your rights back, right away. If an option is not taken within the term in which the label the option has to lift it, it should be gone. Otherwise, it would be an easy way to very easy get the rights of tracks, without having to do anything for it, right? A guaranteed release might be an option.

Questions?

There is so much more to talk about and it’s interesting, but complicated stuff, but I’ll wrap it up now. Hopefully the little voice in your head made some of the clouds around records deal go away. Don’t sign a deal you don’t understand. If you know you don’t know, that’s ok. Read a book like “All You Need To Know About The Music Business” by Donald Passman and follow my Facebook page called “De Dance-advcocaat” (in Dutch only). You can also contact me by filling in the form below.

[contact-form][contact-field label=”Naam” type=”name” required=”true” /][contact-field label=”E-mailadres” type=”email” required=”true” /][contact-field label=”Website” type=”url” /][contact-field label=”Bericht” type=”textarea” /][/contact-form]